We interviewed Benedykt Szneider, creative director of Reikon Games’ debut title RUINER, about its marketing-led development, cyberpunk influences and what the soundtrack vinyl means to him.

By Thomas Quillfeldt

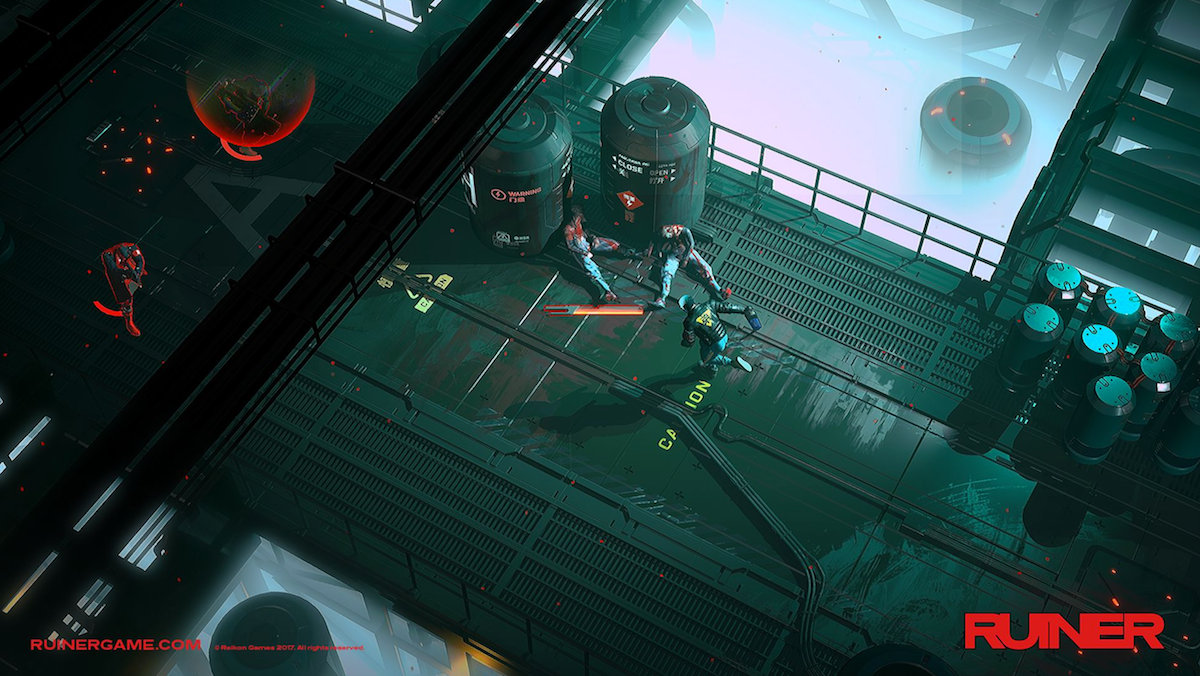

Horizon Zero Dawn’s ‘robot dinosaurs’ notwithstanding, there are few game pitches as concise as ‘cyberpunk Hotline Miami’. Such was the strength of the idea that, around 2015, lured concept artist, logotype designer and comic book creator Benedykt Szneider to the newly formed Reikon Games as it began development of what became 2017’s brutal isometric action game, RUINER.

Published by Devolver Digital and available on PC, PS4 and Xbox One, RUINER is set in the cyber metropolis Rengkok in the year 2091. It sees the player rampage through a world ravaged by corporate overreach, corruption, slavery, murder and the wholesale devaluation of human life.

So far, so cheerful. But what has really set the game apart from the legion of indie releases in a highly-saturated market is its striking look. As Szneider explained to Laced With Wax, whilst the game’s development was iterative and fairly instinctual on the part of the team, there was a deliberate decision made to create bold, iconic marketing images early in the process — codifying the style and core ideas of RUINER before much of the game existed.

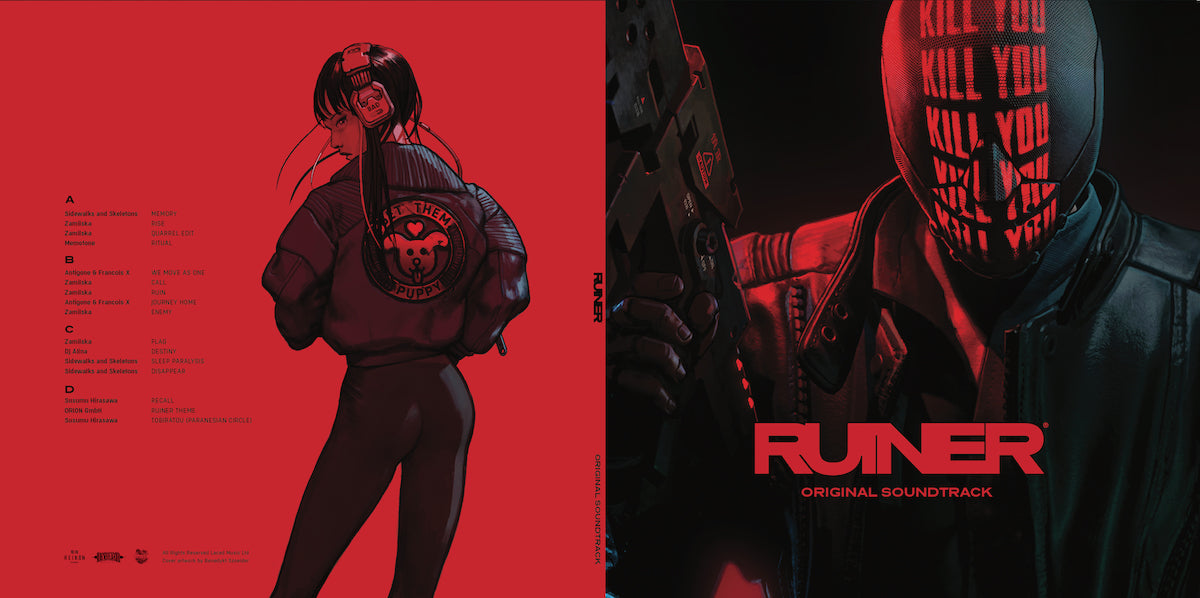

Laced Records is releasing the RUINER soundtrack on 2xLP vinyl (available to pre-order at LacedRecords.com), featuring music from the likes of Sidewalks and Skeletons, Zamilska and Susumu Hirasawa:

A slightly different tracklist is available digitally via Steam.

The road to RUINER

Prior to Reikon and RUINER, Szneider worked as a artist creating marketing assets: first for CD Projekt Red’s The Witcher: Enhanced Edition (2008); and subsequently as part of independent art direction studio HYDRA Warszawa. At HYDRA, he worked on trailers and logotypes for titles including CD Projekt Red’s The Witcher 2 and Cyberpunk 2077, Flying Wild Hog’s Shadow Warrior 2 and 11 bit studios’ This War of Mine; games all being developed (at least in part) in the Polish capital, Warszawa, where Szneider lives and works.

Following the release of the critically and commercially adored The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, CD Projekt Red has ascended to become a significant player in the international games industry. It has also proved to be a fertile garden for Polish game development talent, as Szneider posits: “If it wasn’t for CD Projekt Red there probably wouldn’t be a Reikon Games because so many people worked there at some point and many of them have started their own companies.”

Some of the logotypes that Benedykt Szneider worked on prior to RUINER:

After five-ish years in service-based marketing, Szneider developed a thirst for working on his own game, or at least joining a bigger project. Fortunately, his peers were feeling the same way, which is when a colleague from CD Projekt Red, Kuba Styliński, mentioned an indie game currently in development, sparking Szneider’s imagination with just three words: ‘cyberpunk Hotline Miami’. The answer was obvious: “I’m in!”

Reikon Games was founded in late 2014 by four seasoned game creators: Jakub “Kuba” Styliński, Maciej Mach, Magdalena Tomkowicz and Marek Roefler. Their collective credits include the cream of the Polish video games crop: all three Witcher titles, as well as Techland’s Dead Island and Dying Light. The initial concept that became RUINER was born in mid-2014, with the studio formerly up and running full time at the start of 2015. A starting team of six developers grew to 18 by launch in September 2017.

Szneider first came on board as a freelance artist, working separately from Reikon’s small team: “I joined the project to contribute some initial concepts and exchange ideas about the direction of the game.” After half a year of working in this way, everyone felt it would be beneficial to have him in the office to help directly.

In short order, he became the creative director of the studio’s debut project: “I was integrating with an existing team at a time where there was some idea of the gameplay, and we had a logo and website up and running. People started joining and we formed an environmental art team. It was all very iterative and we learned a lot during that time.”

Not that way — let’s go this way!

Szneider is keen not to claim more than his fair share of credit for the overall success of the game, but it is clear from the accounts of several different team members that his bold vision for the game and direct way of presenting his ideas were vital to what RUINER ultimately became.

Prior to his involvement, the game had another similarly pithy pitch: ‘Cyberpunk Die Hard’. Narrative designer Magdalena Tomkowicz told Engadget:

“At first [the game] started off as a sort of cyberpunk Die Hard adventure, where you hacked your way up a building… We then thought of taking the gameplay direction similar to Hotline Miami and we were still looking for a graphics designer. We found Benedykt… and showed him some early graphical references. He simply told us: No. Let's do this in a different way.”

Szneider recounts that there was a critical meeting at which the team and he had to choose whether he would just focus on art, or whether he would take on the lynchpin role of creative director (alongside Kuba Styliński as game director and Tomkowicz as narrative designer), overseeing aspects of the story, the look of the game, the marketing, the music and so on. (It’s worth mentioning that job titles in game development rarely cover the same list of responsibilities between different companies and projects.)

In spite of this being Szneider’s first game development gig, he was forward and resolute. Indeed, he suspects his naiveté helped: “It was much easier for me to project a vision of the game, but the result of that was that it was somewhat tougher to work with me! I wasn’t 3D-savvy and I had to learn a lot about the basics of art in game development. We had guys that did that very well and handled the technical side of things, which meant I could focus on the concept art, the story and pulling it all together as creative director.”

Fulfilling such a senior role in a small team meant that he barely stopped to sit down: “You’re constantly up and running from desk to desk because everybody wants something from you. It was an exhausting role — although I asked for it! But it was interesting and a challenge to be able to go all the way [through to release] considering the resources we had. We pushed really hard.”

A few members of the Reikon Games team at PAX West 2017. Left to right: Magdalena Tomkowicz, Karol Wieczorkiewicz, Jakub Styliński, Benedykt Szneider and Adam Sikora:

The proverb ‘the night is always darkest before the dawn’ seems to fit almost every successful video game project: there will be a period during development when the team cannot envisage the game being finished at all, let alone to an acceptable standard. Szneider hints that he reached that low point with RUINER, but that despite that — and despite having had to spend years immersed in the oppressive world of the game — he is anxious to crack on with the next Reikon Games project because of the bonds he formed with his teammates. “When we started, there were not a lot of people on the team so everybody took on several roles and had a lot on their shoulders. It was a bit chaotic, but we pulled through. It feels like we’re a band of soldiers that went to war together. We now know how to work with one other with less friction.”

If he did have a case of ‘imposter syndrome’ during development, he’s a lot happier talking about the game now that it’s out: “It’s much more fun now [to reminisce] — the work is out there so you can’t hide.” He says that Reikon are straight onto the next project, throwing around ideas and artwork. At this embryonic stage, he feels like being able to just draw feels like a vacation.

U Got The Look: How marketing can drive game creation (without it being cynically motivated)

Over the last five years, the sheer quantity of games released has arguably become overwhelming (reportedly 7,672 on Steam alone in 2017) meaning that the all-important task of getting the attention of the media and gamers is increasingly difficult. In a recent discussion with veteran game director Amy Hennig (Uncharted series), published by Polygon, Campo Santo’s Sean Vanaman (Telltale’s The Walking Dead and Firewatch) said:

“The hardest thing to do in this business, full-stop, is to get someone to know about your game. It’s harder than making it. It’s harder than shipping it. It’s harder than fixing bugs.”

Whilst it hasn’t made waves like 2017’s indie breakout PlayerUnknown's Battlegrounds (few games have), RUINER has caught people’s attention thanks to its indelible style. There was strategy behind that success: although he had plenty on his plate as creative director, Szneider was adamant about holding onto the reins of the marketing (where his previous games experience lay). “I had trouble letting go of the marketing side because I had the feeling we needed to be precise about what we showed — and that the game would distinguish itself once people saw it.”

There has been plenty of controversy in recent years around video game marketing and how it feeds into commercialised ‘hype’ culture; the problem usually comes when fans’ sky-high, unchecked expectations collide with the sobering reality of the final product. Behind those controversies lies the fact that the realities of game development are little understood by the public, or even by fervent gamers.

But early marketing pushes by developers and publishers aren’t necessarily as cynical as all that. In the aforementioned Polygon interview, Amy Hennig points out that a trailer produced early in development can serve as a useful “animatic of [the developer’s] intentions”; Sean Vanaman replies that “we build trailers to set the tone for the rest of development.”

This philosophy was something Szneider had internalised early in his creative career. Drawing his own comic books at a young age, he often eagerly jumped the gun by creating the covers and logotype near the beginning of the process, imitating his favourite ‘proper’, commercially available comics (Marvel, DC and the like) by adding the price and other signifiers of professionally complete products. Whether out of impatience or to give himself something to aspire to, he enjoyed baking the pie crust before mixing the filling.

One of Szneider’s published comic books, Diefenbach:

In a similar fashion, Reikon and Szneider decided to define RUINER’s style, lead characters and the feel of the game world through what was essentially reverse marketing, with assets being settled on at an early stage of development. “Maybe this is my USP, the thing I bring to the table: to envisage the product as if it were already complete.”

He implies that having the marketing tail wag the development dog was only workable because it was a debut project: “It’s always fascinating to work with a blank page because you can be a jerk, be a joker. You can give the impression that you know what you’re doing [through trailers etc.] — although it’s important not to bulshit people.

“RUINER was a perfect example of [marketing-driven creation]. The gameplay department needed time to ‘find the fun’ and, because Reikon was a small team, this meant that it was an iterative process — more organic than a big design doc-driven AAA game. The marketing had to be done at some point, so [my team and I] started with that.”

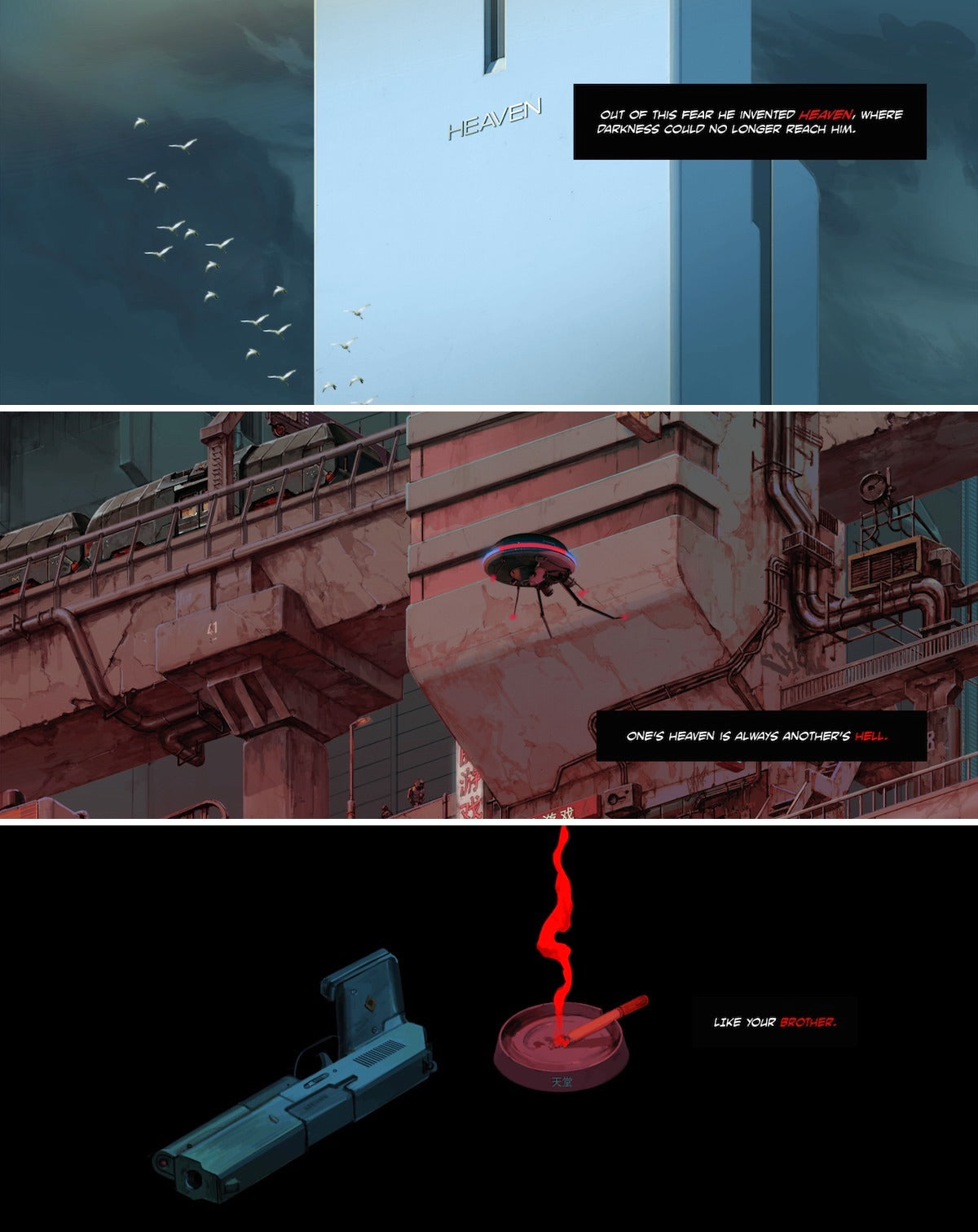

Szneider and his friend Piotr Niklas from HYDRA (the marketing agency that Szneider left to join Reikon) created the RUINER logotype (the font is Presiclav, if were curious). This was followed by the game’s website — Ruinergame.com — which features a scrollable motion comic setting up a mysterious cyber-noire story about a brother who “knew too much”. We recommend you take a minute check it out…

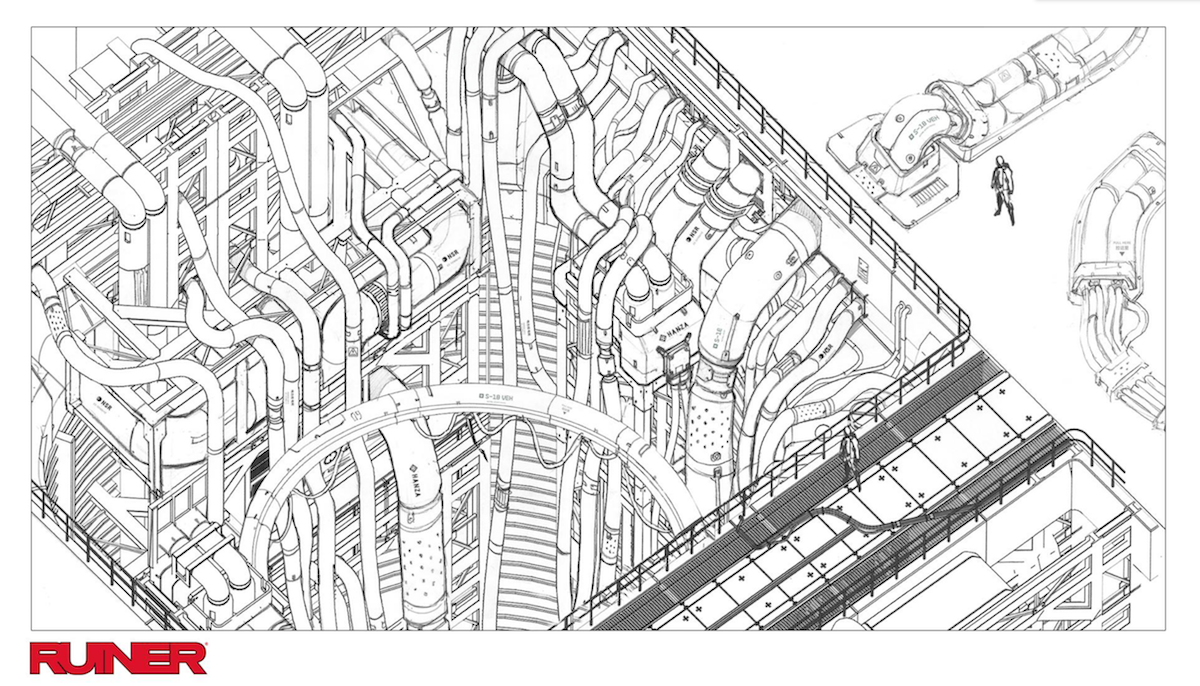

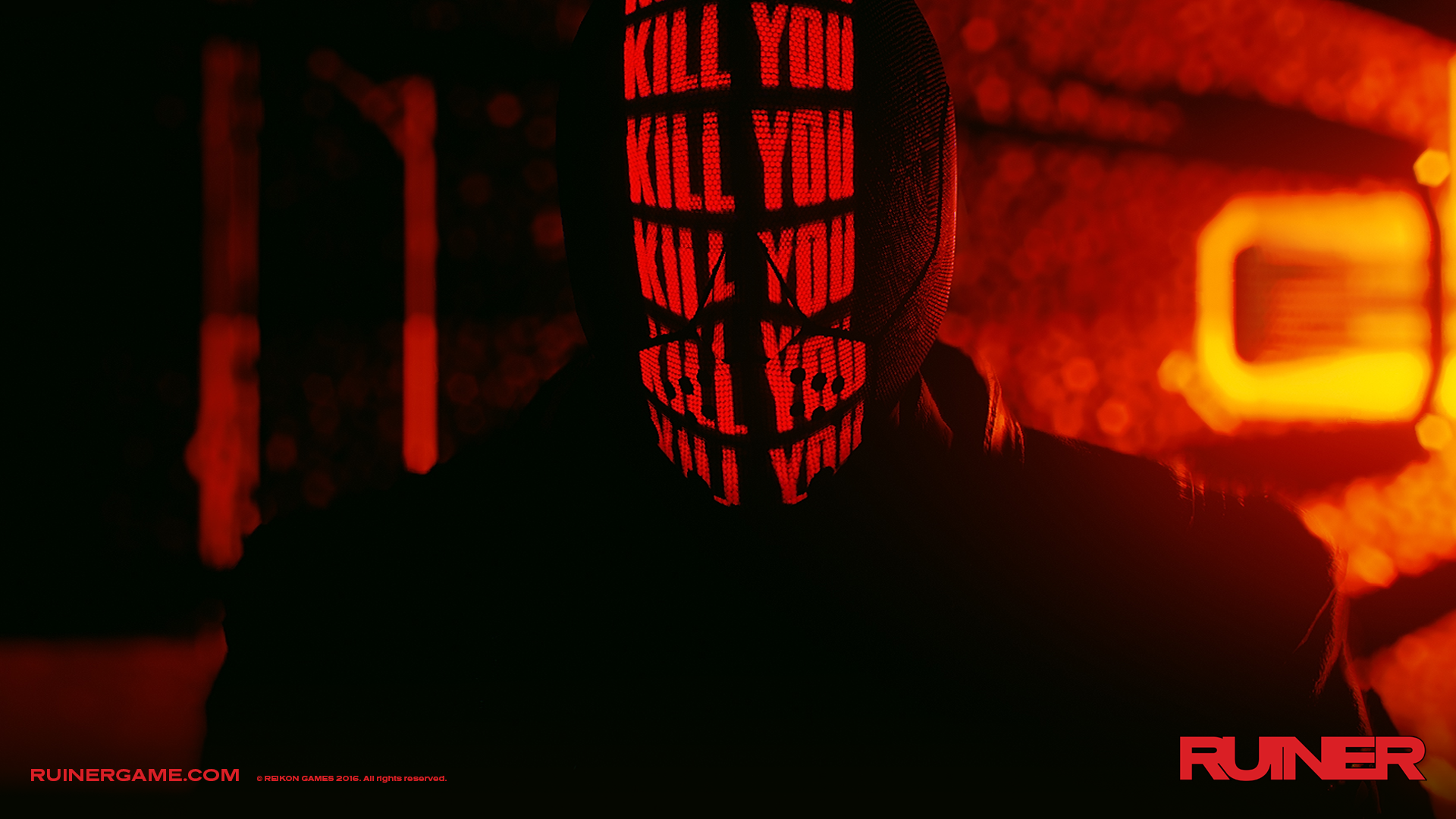

A few glimpses of the scrollable motion comic at Ruinergame.com:

Even some time after release, Szneider is obviously still inspired by the stark clarity of the ideas that pervade RUINER’s marketing, all presented in an eye-popping combination of red, black and blue-grey. One of the first ideas to hit him was that of the stylish, mysterious hacker simply named ‘Her’ sending the protagonist the message: “We were never friends”.

‘“Her’ is much more interesting than the player character because he’s just a lump of meat being used by everybody. [Game director] Kuba and [narrative director] Magda wanted to have a masked protagonist, and I came up with the idea of a helmet that basically displayed GIFs,” a notion inspired by Szneider’s Tumblr wall, which had become a mess of flashing, looping images — like a jumbled up stream of consciousness.

Thus was born the idea of the main character’s ‘display helmet’ featuring a screen that cycles through a hodge-podge of provocative words, questions, phrases and eerily worded platitudes. Although these are literally written on our protagonist’s face, they don’t correspond to his thoughts or reflect his personality, instead being broadcast by the hacker, Her:

The words projected onto the mask and also spread throughout the marketing assets serve as a game of cyberpunk word association, designed to intimidate and confuse. Phrases include:

- HELLO DARKNESS

- GET THEM, PUPPY!

- POTENTIAL COUNTS FOR NOTHING UNTIL IT’S REALISED

- YOU ARE BEING PLAYED

- YOU THINK TOO MUCH

- NO WAY OUT OF THE MAZE

- NO DRUGS NO FIREARMS NO FUTURE

- YOUR SALVATION IS NOT HERE

- I CTRL YOU

The prominent bluntness of the messages has been central to boosting awareness of the game, especially on social media, where such eye-catching images flourish; RUINER might just be the first game where one of the lead developer’s penchant for attention-grabbing GIFs helped shape the development itself.

At the time of writing, District 9 director Neill Blomkamp has a RUINER marketing image as his Twitter profile header:

Because RUINER leans on the cyberpunk tropes of all-powerful corporations and ever-present, dehumanising corporate branding, it feels entirely fitting that the art of marketing and branding played such a pivotal role in it’s genesis. How Szneider perceives the game’s story is in keeping with the shallowness of modern marketing: “It’s not very deep, and it shouldn’t really be weighed separate to the gameplay. I think we did just enough to create some context for the brutal, vicious action of the game.

“[That initial marketing work] felt right. It felt interesting. We weren’t really sure what we were doing but we felt it was going to be OK — we just needed to inject more of that intense atmosphere from the marketing assets into the game, which was a tricky but interesting process.”

When it came to having a red-coloured user interface (rather than the standard white that helps icons stand out during play), Szneider admits: “It wasn’t the least controversial idea in the room... some of the team weren’t happy about it, but I was sure that a few complaints about a red interface wouldn’t be as bad as if the game lacked character. All the time we had to balance between those things.”

Another choice they made was having mission updates flash across the screen, obscuring the player character:

“We knew that the more potentially unintuitive stuff we put in like that, the more intense the product would be. I think we made it a little too intense in a way, but I also know that that intensity is an advantage of the game. That was the product, that was our mission.”

RUINER red and yummy plastic

You simply cannot escape just how red RUINER is (for the curious, it’s #DB1229 in Adobe Photoshop). Szneider jokes: “There will definitely be no more red in the next game — everybody’s so tired of it! Although I don’t think we’re going to escape having blood in our next game so…”

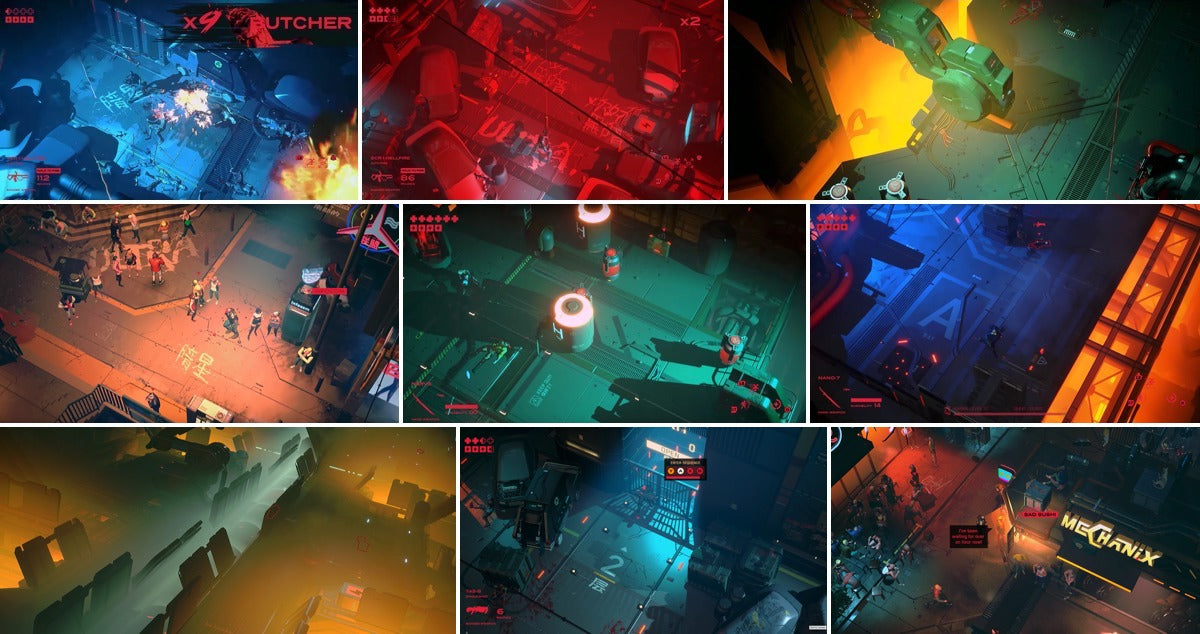

Aside from the ‘RUINER red’ fonts and UI elements, there are only a handful of colours used throughout the game: ever-present, shadowy black; green and blue metallic greys; various neon colours; and red, blue, green and orange lighting.

“In terms of colour choice, I established some key ideas through the marketing at the beginning, but after that our 3D environment artist Karol Wieczorkiewicz, who is very colour conscious, took over; only on very rare occasions did I step in to ask for alterations. Ultimately, establishing the game’s environments rested on his shoulders, not only artistically but technically as well. He would keenly wait for the next update to the Unreal Engine 4 tools, and worked like crazy right at the end of the project to add volumetric fog.”

Szneider did have a hand in lighting cutscenes, giving him a chance to convey his ideas about lighting and establishing the mood. “We agreed some rules about lighting and colours, for instance we wouldn’t have too many colours on-screen at the same time. A lot of cyberpunk games are loads of neon colours, green and violet and so on, and they all get mixed together. We decided to limit it to two colours at any point because, with all the shooting, it’s going to be chaotic enough already.”

RUINER impressed the Unreal engine makers Epic Games so much that the company gave Reikon an Unreal Dev Grant — a program to give no-strings-attached funds to talented creators.

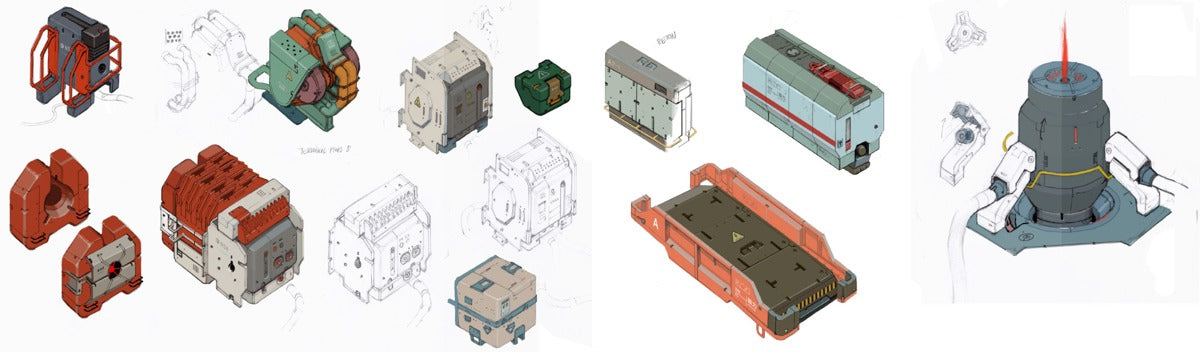

Wieczorkiewicz’s idea, garnered from Alien: Isolation, was to use more complicated polygonal meshes to give things a sense of roundness. Szneider explains that this meant “even a small fan on the wall looks a bit designed and nice. Things are yummy in this game — you want to lick them, to taste them. There’s nothing in this game that was visually designed with realism in mind. All the materials (cars, barrels, dumpsters etc.) we made to look a bit plasticky because they catch more light and look more metallic.” Another vital team member was the sole modeller, Jakub Mularski, and Szneider credits he and Wieczorkiewicz for making the game’s style what it was.

Concept art for objects in the game:

Original, moi?

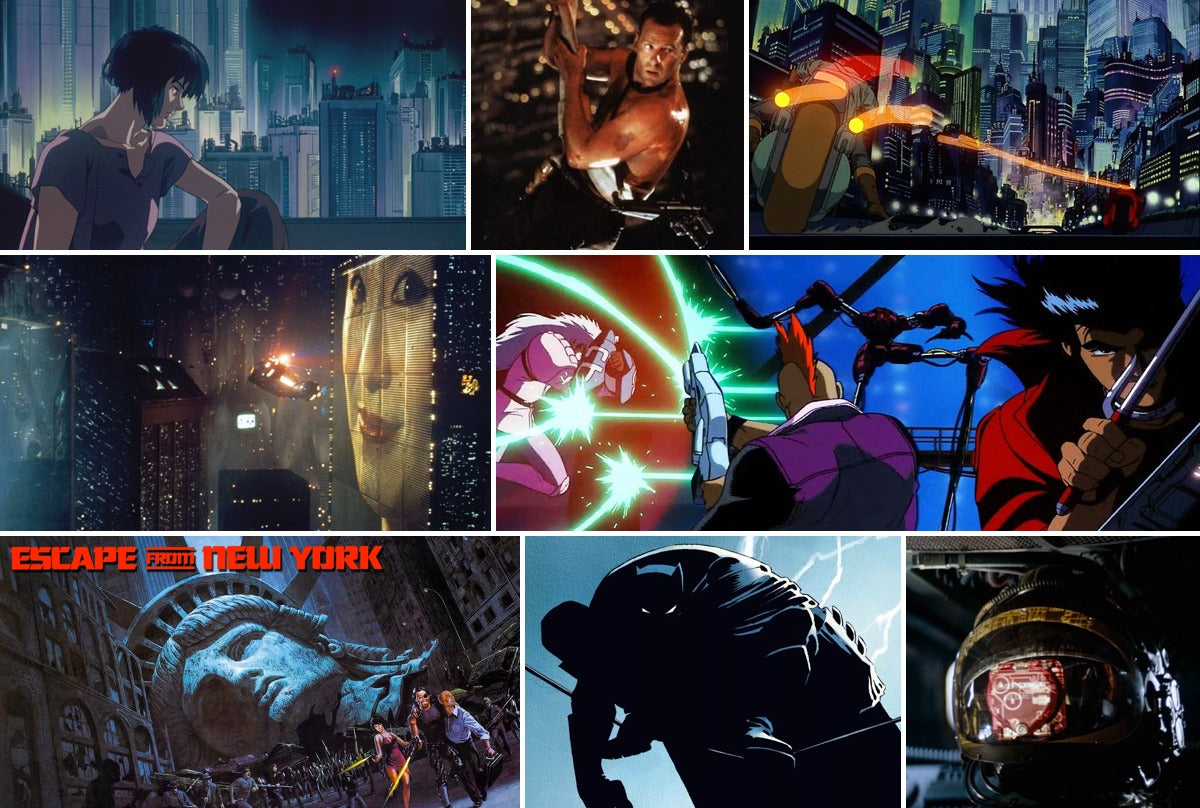

Narrative director Magdalena Tomkowicz and Szneider were both products of the ‘80s and ‘90s and brought plenty of pop culture influences to the table both consciously and subconsciously — movies and comics like Ghost in the Shell, Akira, Blade Runner, Alien, Die Hard, The Dark Knight Returns and Escape From New York. It wasn’t inevitable that RUINER would end up as a dark cyberpunk adventure, but the pair’s shared interests in technology, urbanity and anxiety about corporatisation helped push the game in that direction.

From left to right in descending rows: Ghost in the Shell, Die Hard, Akira, Blade Runner, Cyber City Oedo 808, Escape From New York, The Dark Knight Returns and Alien:

Szneider is perfectly happy to admit that the game’s story and world are echoic of other works: “I don’t think there’s anything original about it! Everyone does it all the time — you become heavily influenced by things during your impressionable years and then you constantly project that onto your professional work.” That said, he still has faith in RUINER's ability to stand out in a crowd of other games: “I don’t think there’s much around that looks like it.”

During the game’s hectic production, he didn’t go out of his way to revisit and study the Japanese cyberpunk anime films of his youth (“my usual morning as a teenager was sitting on the couch with breakfast and putting on the VHS of Ninja Scroll”) preferring to trust his instincts that the characters he was drawing had their own thing going on. “That’s the best stuff: where you know something includes aspects of a character you liked from a favourite show, film or comic, but because you’re not deliberately referring to the original picture, it goes through your own filter and comes out cool.”

Geminus/Sick Sisters from RUINER:

“The cool thing about working on a [small indie] game like RUINER is that you don’t have much time to sit around and smell the flowers. I had to draw concept designs within a few hours, and we rarely did different versions. You must be all over the place, all the time, working concurrently on things like the pacing, the music, the interface, the animations… It’s a great adventure.

“From what I’ve heard, Japanese animators work under constant time pressure. They draw fast, and I was always really inspired by that and try to draw as fast as I can and not really dwell on every little detail. Some of RUINER's characters could be more ‘finished’, but so what? It’s the kind of game where you shouldn’t worry too much about it. It isn’t a museum piece. The game has its flaws but it’s energetic and that’s all we cared about. I’d love to have another year longer to work on it, but you have to say ‘stop’ at some point.”

Cyberpunk, from West to East

Sci-fi and cyberpunk tropes have travelled from West to East (most significantly from America to Japan) and back again many, many times over, so it’s no surprise that RUINER is a mashup of global influences — albeit developed in Central Europe. Szneider himself grew up in the Polish countryside (under the communist Polish People's Republic until the collapse of the Soviet Union), sharing comic books and movies with a friend. Pre-internet pop culture would reach them from the East and West, but he didn’t necessarily think too hard about the delineation.

In their Engadget interview, Szneider and Tomkowicz distanced RUINER from comparisons with the most widely-cited example of Western cyberpunk, at least aesthetically: Blade Runner. Their point is that Blade Runner’s 1982 vision of 2019 (based on Philip K. Dick’s 1968 vision of 1992 [2021 in later editions] in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?) is now, in the late 2010s, pretty out of date — untangle that one if you can.

In simpler terms: Ridley Scott’s vision of the future was especially resonant in the 1980’s, but is less so now. After all, Rick Deckard has to call Rachel from a fixed line public pay phone, rather than everyone carrying a smart device. What RUINER borrows from Blade Runner, therefore, is more limited than might first appear to be the case.

It goes without saying that Szneider’s a fan, but he couldn’t stay awake during a recent rewatch: “How many times can you watch [Zhora] running through the glass? Its influence is undeniable, but [as a cultural mirror] it doesn’t serve us as it did in the days of no internet and VHS.”

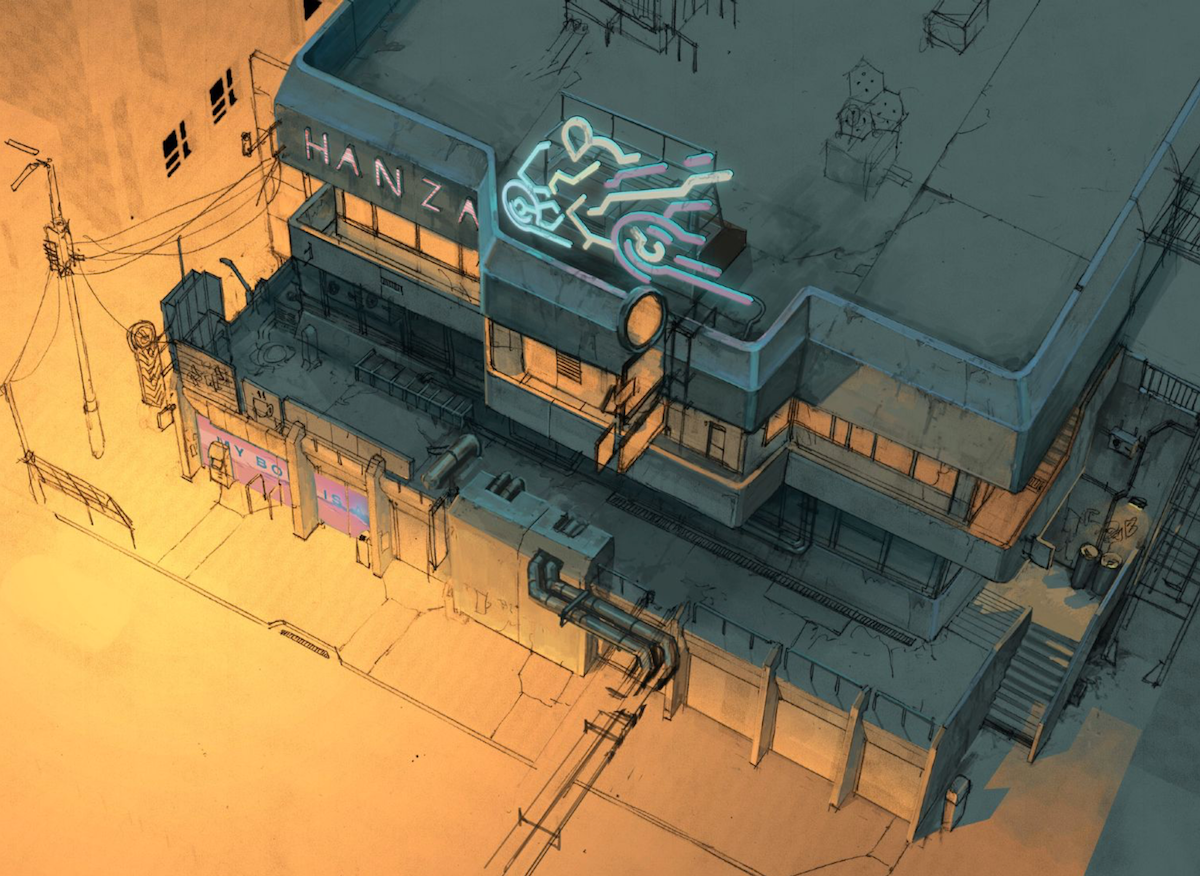

Perhaps the most Blade Runner-esque of RUINER’s in-game art:

Perhaps to the benefit of RUINER, the conversation around the state of cyberpunk fiction was in full swing during 2017 thanks to the release of Denis Villeneuve’s Blade Runner 2049. The Reikon team went to see the movie on its launch day, but by that point their game was done and dusted. Szneider respects Villeneuve’s willingness to tackle hard sci-fi themes in a big budget blockbuster, even if that approach didn’t work out so well in terms of the film’s box office appeal.

At the time of writing in 2018, gamers are eagerly anticipating Polish developer CD Projekt Red’s Cyberpunk 2077 — a competing expression of cyberpunk through a 21st Century lense. The game is being consulted on by Mike Pondsmith, creator of the tabletop RPG Cyberpunk 2020, which was itself heavily influenced by the written works of William Gibson, Bruce Sterling, and other ‘Mirrorshades’ authors — the literary branch of Western cyberpunk:

But it was to the East that Szneider and co were looking primarily for inspiration, and RUINER resembles the 1982 manga and 1988 anime Akira as anything else: “I’m definitely for the Eastern side of cyberpunk — no question about it.”

He recognises that anime has become hugely influential, including in games that are more cheerfully colourful than RUINER, such as Blizzard’s Overwatch; he also sees artists mixing Eastern and Western influences on sites like Artstation.com. But he was keen on sticking to the cursing, blood and gore and fast pace of the darker, more niche cyberpunk anime: “There’s not a lot of that around [in Western media], so that turned out to be something that distinguishes the game. In that sense, it’s ‘mission complete’.”

One source of inspiration for Szneider that was new to him was the Japanese early ‘90s cyberpunk anime, Cyber City Oedo 808 (available on YouTube), directed by Yoshiaki Kawajiri (Ninja Scrolls, Wicked City, The Animatrix). In conceiving the ‘GIF mask’ of RUINER's protagonist, Szneider referred to the flashing GIFs cycling on his Tumblr feed: “That’s where I got the idea for ‘KILL YOU KILL YOU’, but I didn’t realise it came from Cyber City — of course we made all of the mask images from scratch, animated by Piotr Niklas.”

“Separate to cyberpunk... I was at the Angoulême International Comics Festival a few years ago and I simply wasn’t inspired by the European-drawn books I was seeing — they lacked dynamism. I was already working on RUINER which was fast and all about breaking everything; our influences reflected that. But then I saw some work by young artists from Korea and I was like ‘OH!’ The work was pulsing — it gave me my electricity back. I’m more and more inspired every time I see the work of certain artists from Asia, particularly Korea.”

He points to Boichi’s Sun-Ken Rock as a prime example of this dynamism (WARNING: even a cursory search for Sun-Ken Rock will reveal some seriously saucy NSFW images):

“Those guys break the pages. They make it look easy, but understand that it’s such a hard thing to achieve this level of dynamism in comic books. It seems mechanical — as if a machine drew it — but it’s hand-drawn.”

This could be Rengkok or anywhere...

As with the setting for American author William Gibson’s cyberpunk classic, Neuromancer — Chiba City, Japan — RUINER is set in a dystopian Southeast Asian cyber metropolis: the fictional Rengkok in the year 2091. According to Reikon’s Magdalena Tomkowicz, its name comes from the Japanese word ‘rengoku’ (煉獄), meaning ‘purgatory’.

The team’s approach to gathering reference material from Eastern sources was relatively casual. In and around development, game director Kuba Styliński and Tomkowicz did travel to Japan, though not for any kind of visual research (and Szneider didn’t join them). “It was always: ‘Yeah, maybe we’ll include some Asian ideas’. I was looking at Bangkok via Google Maps, and the city has a monorail driving through the city and a lot of visual noise going on — so we drew on some elements.”

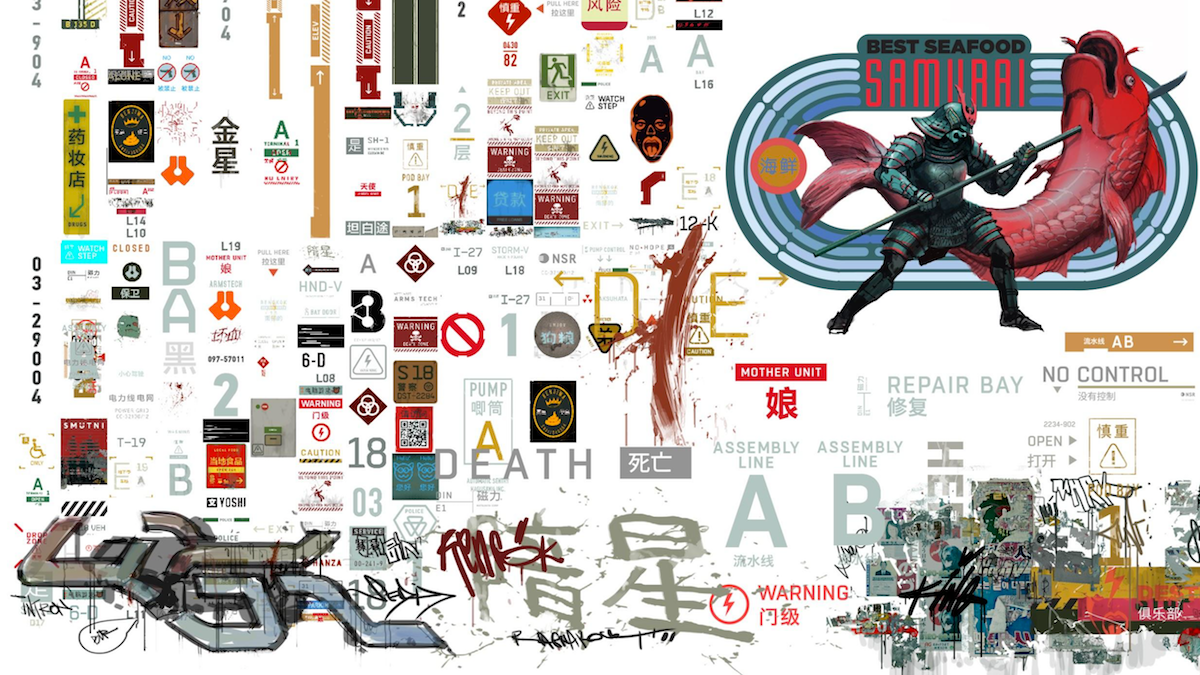

That’s not to say that the team indulged in lazy Orientalism or lacked taste when including Asian elements. Szneider was touched when a Chinese fan praised the game for its subtle inclusion of Chinese letters and slogans: “He said that we didn’t just use the Asian stuff that attracts tourists: monks and pagodas and so on. He felt that we successfully captured the urban atmosphere: the chaos, the colours, the greediness, the craziness of it, and that made him want to give us a shout out.”

Good science fiction is supposed to reflect the times of the authors, and Szneider points to the appearance of Chinese language on Hollywood movie posters and elsewhere as a sign of the increasing reach of China in the 21st Century: “RUINER is just amplifying that to a new level because our game takes place 70+ years in the future.

“It’s not supposed to be particularly prominent because Rengkok is a shitty city; the part of town the game takes place in is not very important in the grand scheme of the universe. It’s just a bus stop. It’s not the beautiful metropolis that New York is in Hollywood movies. The vibe is the most important part.”

He makes clear that the modern anxieties that serve as a backdrop to RUINER's action are globalisation and landfill acculturation — not nationalistic xenophobia. “[In our future, and the future of RUINER] the whole world is going to look pretty much the same everywhere because everything is being built by everyone and we are moving towards a monoculture. It’s going to be hard to see the differences between cities, whether they’re in Asia, Europe or wherever. It’s a pile of concrete with people locked inside.”

In this light, Rengkok could just as well be anywhere — even in Poland. “Cities change their names, so why not? Somebody could buy our capital city and change the name.”

Various logos and signage used in the game:

Poles apart?

All Szneider’s video game-related work has centred around the hub of games companies based in Poland’s capital, Warszawa, and he’s thoughtfully aware of the influence of Polish culture on RUINER, as well as on other cultural exports such as The Witcher franchise.

When Laced With Wax interviewed pioneering comic book artist Śledziu — a friend of Szneider’s — he spoke about the effects of the fall of communism on pop culture and comics, both within and without Poland. The two are of a similar age in their mid-40s, and are cognisant of the ‘Polishness’ of their work. Szneider explains: “A lot of RUINER is influenced by Reikon being a Polish developer. It might sound weird, but it’s to do with the atmosphere and the way some of the characters look, for instance the Creeps.”

“RUINER's Rengkok isn’t special: it’s just an everyday city, maybe a bit less dirty and with a heightened cyberpunk atmosphere. It’s very foggy, as it can be in Poland. The streets may seem quite Asian-influenced, but the volume of concrete everywhere and the neon lights speak to Polish back alleys. We’ve grown up with this cosmopolitan mix of everything: [in a typical Polish city street] you have a beggar missing a leg sitting next to a Lexus, next to a butcher’s shop, next to beauty parlour. Maybe it’s less glamorous in Poland than in other cities, but it seems to be the same everywhere.”

A concept image of a Rengkok street:

Notable Polish video games that have travelled at least as far as the UK include the sobering This War of Mine (set in war-torn Bosnia but developed in Poland), the morally grey Witcher games and the ultra-violent Shadow Warrior series. Szneider says: “I wouldn’t personally put RUINER in the same league as some of those other titles, but I guess we tackle some of the same things. Our approach was rooted in what we liked as kids — it’s less about being Polish and more about the culture that kicked us in the ass when we were young.”

He finds it a bit of a stretch when asked whether he thinks that the dark history of Poland during the 20th Century seeps into Polish games across the board: “You don’t have that strong an opinion on those things [e.g. Soviet communist dominance, democratisation and capitalism] — you just live through them.

“[The games mentioned] deal with violence, bleakness and world building in a different way to, for example, games from America or the rest of Europe. That bleakness is here [in Poland] but it’s not something that is uniquely ours; it’s something that happened because of the inrush of capitalism after 1990.

“The fall of communism was an interesting time for me: I remember a very grey reality, but the capitalism that replaced communism is like a machine. People seem much happier now — they can travel, they don’t have to pretend to like a political party — but at the same time you can still relate to the past in some ways because there’s a lot of misfortune and unhappiness caused by capitalism. The whole country is a bit divided between younger people who want to move forward, and those that are less keen about modernisation and globalisation. I can relate to both sides.”

Szneider comes back to The Witcher series, the video games of which are based on the hugely successful novels by Andrzej Sapkowski — Poland’s J.R.R. Tolkien — mostly written during the post-communist 1990s. “Nothing is black or white in Sapkowski’s books; everything is a bit grey and that is reflected in the games.”

A screenshot from the opening of The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt:

“As well as making great games overall, CD Projekt Red’s biggest success is making the player unsure as to how every story encounter is going to end: for example, maybe that monster is going to talk to you instead of fighting you. That was something new, to me. Yes, The Witcher games are bleak, but they’re more down to earth than other RPGs because of this approach — the weakest part of Lord of the Rings is the simple ‘good versus evil’ dichotomy.”

Music to watch creeps by

The soundtrack for RUINER — comprising a compilation of tracks that Laced Music worked with Reikon and Devolver Digital to license — was picked by various members of the development team including Szneider: “Because we didn’t have a music team, we spent some time working out where each track goes ourselves. Everybody chipped in ideas.

“I spent a couple of weeks working on the [scrollable motion comic] for the website and was listening to Susumu Hirasawa’s music. It felt dirty and humanistic and out there — it really helped me to get in the mood. I bothered everyone about how perfect it was, and we used “Island Door (Paranesian Circle)” in an early internal demo; after which everyone wanted it in the game. Danny at Laced and Magdalena Tomkowicz worked for a year to get permission from Universal Japan.”

The Susumu Hirasawa track “Island Door (Paranesian Circle)” takes up most of Disc 2 Side B on the vinyl, and isn’t included in the digital Steam soundtrack:

“I think it helps show the mellow side of the character. It was important for me to have a little bit of peace, a little bit of serenity in the game. Not to be at peace, but to be more humanistic. I wanted this guy to be a sad, working piece of meat and he doesn’t know what the fuck is going on with his life.” He references the ‘Major versus tank’ scene from the 1995 anime Ghost in the Shell, which is underscored by surprisingly mellow and mournful soft synths:

“For me, those are the scenes I’m looking for — that was my input into the soundtrack. On the other hand RUINER has a lot of energetic and hardcore music that was mostly picked by the game director, Kuba Styliński. He picked the tracks by [Polish independent electronica artist] Zamilska and [London-based ‘Witch House’ artist] Sidewalks and Skeletons [the alias of musician Jake Lee]. It fits perfectly in the game, even if it’s a little too hardcore for my tastes!”

Red hot wax

We’d love to tell you that Szneider spent months slaving over custom artwork for the vinyl package, but as you’ll hopefully have garnered from our exploration of RUINER's art style, the truth is that he already had it in the bag: “It was very simple [to finalise the art for the vinyl]. I put it together a month before the release of the game whilst working on marketing assets and other merchandise, like the Special Reserve Games figurine.

“Having the hacker girl Her with the red background on the back worked well because she’s the reverse of the [unnamed] player character — that was really important to convey. And the theme of the game fits the duality of the vinyl (two discs, two sides to a disc), so it was a no-brainer.”

The RUINER soundtrack vinyl (left) back cover, (right) front cover:

“The team at Laced Records were very supportive and encouraged me to do what I wanted. I felt from the beginning that it was going to be a great product and I can’t wait to see it in print. Maybe somebody could have created some great custom art just for the vinyl, but I don’t care — I didn’t want to dilute the visual universe of RUINER.

“When I heard from Devolver that we were going to get a vinyl and a special edition, I thought ‘the world has changed’ because when I was young, only cult products that had been out for over 10 years like Akira or Ghost in the Shell had special editions or vinyl releases. The amount of geekiness in the world today is overwhelming. For me it’s mind-blowing stuff. I love seeing stuff from the game in print, which you don’t get as much of a chance to do nowadays — I want to cover myself with as much red and black merchandise as I can!”

The RUINER soundtrack vinyl gatefold:

“I see it as another great opportunity — a dream come true — because I may not have the chance to design a vinyl album sleeve again. I’m thankful to Danny and Laced Records for making this happen — this is the best piece of merch we’ve done and I’m very proud of it.”

Szneider himself has tried and failed to get into vinyl record collecting by way of his passion for Norwegian black metal; although, rather sweetly, he does listen to fairy tales on record with his two-year-old daughter. With any luck, the RUINER vinyl (due to ship late Q1 2018) will be the spark he needs to start his collection in earnest — but it’s probably going to be a while before he’s in the mood to aurally revisit the dark, dank streets of Rengkok.

Benedykt Szneider is Creative Director and Concept Artist for Reikon Games’ RUINER – Artstation.com/szneider | Twitter: @BSzneider

The RUINER soundtrack is available on 2xLP vinyl from LacedRecords.com, featuring music from the likes of Sidewalks and Skeletons, Zamilska and Susumu Hirasawa.

RUINER is available on PC via digital outlets like Steam, GOG.com and Windows 10 Store; as well as PlayStation 4 and Xbox One.